Languages, Travel

English Everywhere Everyone

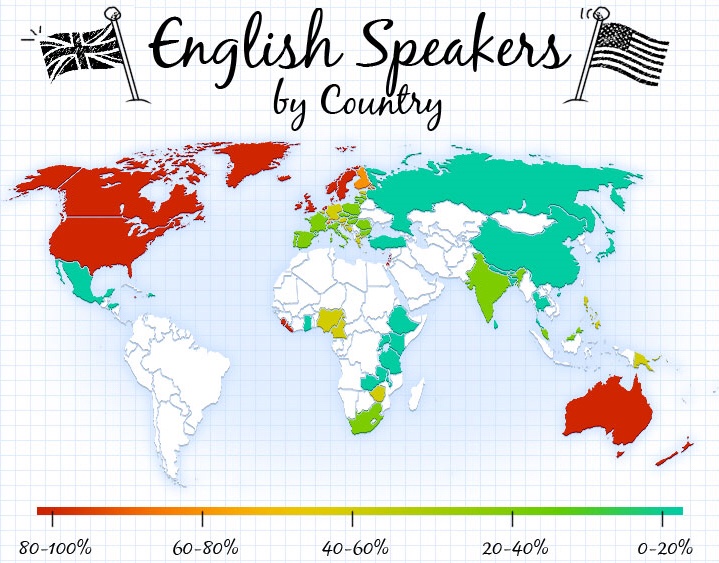

If you’ve done much traveling in the last 20 years, you’ve probably noticed that English is just about everywhere. Out of the world’s 7.5 billion people, 1.5 billion speak English — that’s 20% of the Earth’s population. In 2015, out of the total 195 countries in the world, 67 nations have English as the primary language of ‘official status’. Plus there are also 27 countries where English is spoken as a secondary ‘official’ language.

There are 6,909 distinct languages in the world (according to SIL Intl). What are your chances of speaking English? Wow….Now if you’re lucky enough to be one of the 350 million native speakers of English, you really have no idea how fortunate and privileged you are that much of the world has conformed to this one language.

Unfortunately, it’s not super clear or obvious how English has become so dominant. The simple answer you’ll often hear is that English is the language of commerce. Let’s dig a bit deeper and take a look at some of the different theories and explanations from around the internet that make a bit more sense:

1) Its original Germanic base has been mixed with the Roman vocabulary, giving it “the best of both worlds”–an extremely rich dual arsenal of expression unprecedented in history. English has a long and fascinating history that spans wars, invasions and influences from around the globe. Cultures that have helped shape modern English include Romans, Vikings and the French. For this reason it’s a hybrid language comprised of Latin, Germanic and Romance elements. English (in fact more than 95 % of words are mixture of Latin + Greek + French)

2) It’s extremely laconic (succinct). Sentenced translated from English into other languages take up at least 30% more space. English words are concise and so are its sentences.

3) Absence of a sophisticated grammar system (present in other languages, such as Slavic ones) makes it not only efficient but adaptable to new concepts and technologies. It’s one of the most adaptive languages on earth. A noun can be easily turned into an adjective or a verb, and vice-versa, without sacrificing expressiveness or literary beauty.

4) It’s spoken by the most influential and powerful countries on earth, the USA and the UK. But this is no accident: I actually believe that the privileged status of these Anglo nations is in large part *due to* speaking a language as elegant and adaptive as English, as strange as it sounds. When you have a language as remarkable as English, it’s really no surprise that it would become a potent tool both for Shakespeare and for Bill Gates. Whether we’re talking about movies, art, literature, IT, technical stuff, or science, English is always at the forefront of expression. This proves that, apart from the political status of its speakers, the language itself has certain remarkable properties that make it, objectively, the best language in the world.

5) It’s really flexible – Non-native English speakers who learn it as a second language often comment on how many ways there are to say things. That’s because English doesn’t discriminate – you can use it however you like. Countries like Singapore have taken this concept to heart, inventing an entirely new type of English called ‘Singlish’ that has absorbed facets of other languages like Chinese and Malay. 6) It continues to change – Selfie. Bae. Smasual. All these words are new to the English language but have already become valued members of the lexicon. More than any other language, English continues to evolve and absorb new words that branch out – often untranslated – into other languages. English is definitely a language that knows where the party’s at.

Historical Reasoning: After World War I, Belgian, French and British scientists organized a boycott of scientists from Germany and Austria. They were blocked from conferences and weren’t able to publish in Western European journals. “Increasingly, you have two scientific communities, one German, which functions in the defeated [Central Powers] of Germany and Austria, and another that functions in Western Europe, which is mostly English and French,” Gordin explained. It’s that moment in history, he added, when international organizations to govern science, like the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry, were established. And those newly established organizations begin to function in English and French. German, which was the dominant language of chemistry was written out. The second effect of World War I took places across the Atlantic in the United States. Starting in 1917 when the US entered the war, there was a wave of anti-German hysteria that swept the country. “At this moment something that’s often hard to keep in mind is that large portions of the US still speak German,” Gordin said. In Ohio, Wisconsin and Minnesota there were many, many German speakers. World War I changed all that. “German is criminalized in 23 states. You’re not allowed to speak it in public, you’re not allowed to use it in the radio, you’re not allowed to teach it to a child under the age 10,” Gordin explained. The Supreme Court overturned those anti-German laws in 1923, but for years that was the law of the land. What that effectively did, according to Gordin, was decimate foreign language learning in the US. “In 1915, Americans were teaching foreign languages and learning foreign languages about the same level as Europeans were,” Gordin said. “After these laws go into effect, foreign language education drops massively. Isolationism kicks in in the 1920s, even after the laws are overturned and that means people don’t think they need to pay attention to what happens in French or in German.” This results in a generation of future scientists who come of age in the 1920s with limited exposure to foreign languages. That was also the moment, according to Gordin, when the American scientific establishment started to take over dominance in the world. “And you have a set of people who don’t speak foreign languages,” said Gordin, “They’re comfortable in English, they read English, they can get by in English because the most exciting stuff in their mind is happening in English. So you end up with a very American-centric, and therefore very English-centric community of science after World War II.” You can see evidence of this world history embedded into scientific terms themselves, Gordin said. Take for example the word “oxygen.” The term was born in the 1770s as French chemists are developing a new theory of burning. In their scientific experiments, they needed a new term for a new notion of an element they were constructing. “They pick the term ‘oxygen’ from Greek for ‘acid’ and ‘maker’ because they have a theory that oxygen is the substance that makes up acids. They’re wrong about that, but the word acid-maker is what they create and they create it from Greek. That tells you that French scientists and European scientists of that period would have a good classical education,” Gordin said. The English adopted the word “oxygen” wholesale from the French. But the Germans didn’t, instead they made up their own version of the word by translating each part of the word into “sauerstoff” or acid substance. “So you can see how at a certain moments, certain words get formed and the tendency was for Germans, in particular, to take French and English terms and translate them. Not true for English. Now terms like online, transistor, microchip, that stuff is just brought over in English as a whole word. So you see different fashions about how people feel about the productive capacity of their own language versus borrowing a term wholesale from another,” Gordin said. Sources: https://www.pri.org/stories/2014-10-06/how-did-english-become-language-science http://www.antimoon.com/forum/t14010.htm https://www.lingualearnenglish.com/blog/tips-to-learn-english/10-reasons-english-important-language/ https://www.linguisticsociety.org/content/how-many-languages-are-there-world http://www.stgeorges.co.uk/blog/learn-english/how-many-people-in-the-world-speak-english

Sources: https://www.pri.org/stories/2014-10-06/how-did-english-become-language-science http://www.antimoon.com/forum/t14010.htm https://www.lingualearnenglish.com/blog/tips-to-learn-english/10-reasons-english-important-language/ https://www.linguisticsociety.org/content/how-many-languages-are-there-world http://www.stgeorges.co.uk/blog/learn-english/how-many-people-in-the-world-speak-english